- Home

- Maria Goodavage

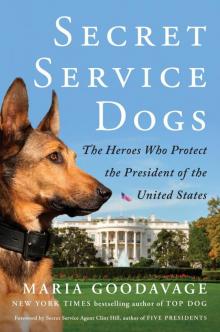

Secret Service Dogs Page 3

Secret Service Dogs Read online

Page 3

“Every day after work, on the long ride home, you wonder: Are we more prepared today than our enemy?”

—

Compared with many military dogs, Secret Service dogs are specialists. Most military dogs perform two jobs: They sniff out explosives and they do apprehension/patrol work. These dual-purpose dogs are known as PEDDs, patrol explosives detection dogs. They’re the backbone of the military working dog world.

Today’s Secret Service dogs do one job or the other. A dog like Astra is not going to take down a White House fence jumper. And a dog like Hurricane won’t be snorting around elevators for explosive devices. Neither dog has time for another job because of their rigorous training and work schedules. And there’s another thought process behind having single-purpose dogs.

“Rather than have a dog and handler be good at everything, we want them to be great at one thing,” Brian says.

Specialization is everywhere these days. Just ask your general practitioner, if you can find one. If anyone has a good reason to specialize, it’s the dogs who protect the POTUS. Mistakes could have dire worldwide consequences. Being focused in one area creates the kind of expertise that can save lives. You wouldn’t want that general practitioner to be your brain surgeon.

The four-legged specialists are almost always immigrants, starting out life in another country, and with another language, often Germanic.

Secret Service dogs, like most military dogs, are usually born and raised in European countries known for their long history of police dog sports like KNPV and Schutzhund. Countries such as the Netherlands and the Czech Republic have been breeding dogs who excel in this kind of work for many decades.

The Secret Service has a contract with a U.S. vendor, which procures most of the dogs in Europe and ships them back stateside. The vendor for all but a couple of years since 2000 has been Vohne Liche Kennels, which also hosts the K-9 Olympics. The northern Indiana facility has contracts to buy dogs for hundreds of federal, state, and local law-enforcement agencies, and to train dogs for departments worldwide.

Secret Service canine crews visit VLK frequently to select new recruits. The Service has a reputation for being extremely choosy.

The dogs the agency selects will train hard and work hard. And at the end of the day, they’ll get to go home with their handlers. Military dogs don’t have that luxury and, unless they’re deployed in a war zone, spend their nights in military kennels.

The Secret Service won’t allow the number of dogs in its current programs to be published. There are concerns about operational security if the wrong people know an exact number. While there are enough dogs to get the job done well all over the world, more canines are in the pipeline as their roles continue to expand.

The elite canine specialists selected by the Secret Service will spend their career in one of the following job categories:

Emergency Response Team (ERT) dogs—The Emergency Response Team is the Secret Service’s version of a SWAT team. It began in 1992, and dogs were added in 2003, partly in response to the 9/11 attacks and concern about possible threats from bombers. ERT dogs function as part of the Tactical Canine Unit, sometimes called the ERT Canine Unit.

ERT dogs are super-high drive, smart, energetic, and courageous. They’re trained in advanced SWAT tactics to physically protect some of the world’s key leaders.

You can call them intrepid or heroic. Just don’t call them attack dogs.

“Attack is a curse word for us,” says Sergeant “Stew,” an ERT Canine Unit supervisor and a former handler. “We ‘attack’ no one. These aren’t vicious attack dogs. These dogs are highly skilled operators that can slow their minds during stressful situations and think.”

Many police-type dogs trained in aggression work are dogs you wouldn’t want to mess with even on a good day. But the Secret Service will only consider canines who are fairly social with people and other dogs, since they’re around so many people, and since they have to work and train with other dogs all the time.

ERT dogs are an option of less-than-lethal force. Instead of being on the receiving end of a bullet, an offender might end up on the receiving end of a dog bite. Not much fun, but better than the alternative.

All ERT canines are Belgian Malinois. Many people mistake Mals for German shepherds, but Mals usually have shorter hair, slightly different coloration, and tend to weigh less, which makes it easier to carry them when a mission calls for it. Malinois are known for being intense and energetic, with fewer hip dysplasia issues than shepherds.

There are no female ERT canines. Brian says that while the males are typically bigger and stronger, “the female dogs are just as good as the male dogs. The aggression we’re looking for comes from the mind, and females have it in similar levels to the males, sometimes even more.”

He says the problem is that if a female Secret Service dog goes into heat during class, the male dogs’ focus will fly out the window. Since the class for ERT is only ten weeks long, and a typical heat cycle is two to three weeks long, that’s a large portion of class to have distracted dogs. (Detection dog classes are seven weeks longer, so if a female goes into heat, it won’t be for such a significant chunk of class. Eventually the female explosives detection dogs get spayed, but not until the Secret Service is as locked in as possible about selecting them for keeps. Male dogs, per military tradition, are usually not neutered.)

Costs for Secret Service dogs run in the thousands of dollars, with ERT dogs tending to be the most expensive. Law-enforcement agencies and military special operations canine programs are always looking for great dogs with this kind of drive. There aren’t usually enough to go around, so they command a higher price.

Most of the dogs have been trained in rudimentary aggression work, but they’re otherwise green. If time allows, canine program instructors, who all double as trainers, work with the dogs for a few weeks more before the ERT canine course begins.

ERT dog handlers have usually been on the team without a dog for about three years before they can apply to be handlers. Their teamwork and tactics have to become muscle memory before they add a living, breathing creature to their arsenal. (There are not currently any women in ERT, although there was one years back. ERT leaders say it’s a matter of the grueling physical standards. So far there have been no female ERT canine handlers.)

The bulk of ERT work is at the White House, inside the fence. The ERT motto, Munire arcem, translates loosely to “Protect/fortify the castle.” The team had come up with the idea for the motto in English, and Stew had it translated by someone who spoke fluent Latin.

For Stew and other members of ERT, the meaning of the motto goes beyond its normal translation: “It may sound crazy, but to us, those two little words mean, ‘Defend the castle/fortress against those who attack.’”

ERT dogs can also protect the vice president’s residence. ERT canines may travel to protect the POTUS and VPOTUS, depending on the mission and situation. But most ERT dogs are not on the road much. When compared with their canine colleagues who sniff out explosives, they are positively homebodies.

Explosive Detection Team (EDT) dogs—These bright, focused, driven, patient dogs are able to detect every known explosive. Their repertoire is constantly changing and expanding to keep a few steps ahead of those who might seek to do harm.

EDT dogs are officially part of the Explosive Detection Canine Unit. These super sniffers are always stationed at the two main entrances to the White House complex for vehicle checks. But their job designation also takes them far from the Executive Mansion. EDT dogs hunt for deadly explosives around the world. They precede the president and vice president almost anywhere they go, and work until they leave.

Unlike military working dogs, they’re not marching into war zones rife with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), with every step potentially being their last. EDT dog handlers contend with a different challenge.

&nbs

p; Most will never find a true explosive device. But their mind-set must be that it could happen anywhere, anytime. Deployed military dog teams have intensive and relatively short rounds in war zones, but EDT handlers and dogs will spend several years seeking out explosives day in, day out. It may be lower stress, but it’s over a far longer stretch, with little downtime.

Secret Service dogs have found explosive devices. But you will not have heard about these “finds.” The Secret Service will officially say only this about the subject:

“We confirm the presence of finds/hits historically, but we decline to discuss further details in interest of operational security.”

It could give the agency a public image boost if these finds were publicized. But it’s not even a question at headquarters: No amount of publicity is worth compromising OPSEC.

EDT dogs don’t get much public attention. They work mostly behind the scenes. They aren’t stationed within camera distance of the White House press corps as the ERT dogs are, or in the thick of the tourists around the White House.

This doesn’t bother the dogs, who are content with a Kong and praise from their handlers. But some EDT handlers wouldn’t mind it if their dogs got a little more public recognition for the important work they do.

Secret Service EDT training assistant Kevin H., a former handler, makes the best of it. When he gets together with his ERT handler friends, he likes to point out one benefit of being EDT:

“ERT has 18.1 acres of land,” he ribs them. “EDT has the rest of the world.”

Personnel Screening Canines (PSCs)—Despite their name, these dogs do not screen job applicants for human resources. If you’ve taken a tour of the White House in the last several years, chances are that you were sniffed by one of these dogs and didn’t know it.

PSCs are all Explosive Detection Team dogs. The PSC gig is something many, but not all, EDT dogs do. Dogs who are too high energy to be sniffing for explosives in a small section of one room won’t make the cut. These dogs have to be cool.

A PSC dog and handler stand behind a louvre screen in the first room visitors enter in the security process at the White House as strategically placed fans gently blow each person’s scent toward the dog. The slightest whiff of explosives can lock down part of the White House.

Personnel Screening Canines Open Area (PSCO) aka Friendly Dogs aka Floppy-Eared Dogs—The official name for these dogs is an awkward mouthful that doesn’t quite match its acronym. Canine staffers have taken to using the other two names, which more accurately describe these affable sniffer dogs. “Friendly Dogs” is the one they tend to use.

Friendly Dogs are the canines you’ll have the best chance of seeing while walking around the streets that flank the north and south grounds of the White House. They’re most often found strolling along Pennsylvania Avenue. You’ll recognize them by their floppy ears (with one notable exception, whom we’ll meet later) and black harness or vest.

If you’re still not sure if a dog near the White House is a mere passerby pet or a real-deal Secret Service Friendly Dog, look at the other end of the dog’s leash. If you see a uniformed dog handler, perhaps wearing a black shirt with the words U.S. SECRET SERVICE POLICE K-9 emblazoned in yellow across the back, it’s a good bet that you’re in the presence of a Friendly Dog.

But tempting as it may be, don’t pet this dog! The dog’s harness warns against petting for a reason. As approachable looking as they are, while they’re on the job they’re hard at work, and their handlers don’t want anyone to distract them.

Like EDT dogs, these dogs sniff out explosives. The difference is that the odors are coming off moving people, not stationary objects. Even the indoor Personnel Screening Canines do their job only when a White House visitor has stopped. But Friendly Dogs track the vapor of an explosive as it moves.

Friendly Dogs go for walks for a living. Rain, shine, sleet, heat, snow, ice—regardless of the conditions, they spend their workdays weaving among tourists near the White House fence line, focused on their mission. If someone smells “suspicious,” a dog will zip behind the person and follow the scent trail until it’s clear to the dog’s handler if something needs to be done.

The Friendly Dog program began in 2014 to expand the circle of canine protection at the White House. These days if someone with an explosive device is going to try to get to the Executive Mansion, he or she will have to contend not only with human Secret Service personnel, but probably with an enthusiastic floppy-eared moving-scent hunter as well.

The agency could have used typical police breeds like Belgian Malinois and German shepherds to do the job. But while some of these dogs can be robustly friendly, they tend to part a crowd when walking through it. This is especially true at a place like the White House, which attracts visitors from around the world, including areas where pet dogs may not be woven into the fabric of everyday life.

For vapor-trailing dogs to work most efficiently, it helps if people don’t try to avoid them. Labrador retrievers, springer spaniels, and other breeds (and mixes) of floppy-eared dogs don’t usually have the same scattering effect as Malinois, who are decidedly unfloppy in every possible way.

The Friendly Dogs are so appealing that it can be problematic. Some tourists see the dogs as a reminder of home, or a warm memory from bygone years, and want to pet them. Others have loads of questions. A few try to get training tips or give advice.

Handlers may answer a few quick questions but always stay focused on their dogs, who are not distracted by questions. After that, a Secret Service officer will usually take over the conversation briefly so the handler and dog can continue their work.

Friendly Dogs are bright, focused dogs with exceptional noses and an abundance of energy. They work intensely for varying amounts of time, and they take frequent breaks, trading shifts with other dogs waiting to take over. Downtime is important so they can recharge and get out of weather that’s not ideal.

It’s also a time for handlers and dogs to reconnect in their vehicles and have a little chat about this and that. After all, the canines don’t get the name Friendly Dogs just because of their ears.

—

The Secret Service was created in July 1865 to thwart counterfeiting—a Civil War–era scourge that threatened the broken nation’s financial and banking system. Despite its inception less than three months after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the agency began with no mandate for presidential protection. It wasn’t until 1901, after the assassination of President William McKinley, that safeguarding the chief executive became part of the Secret Service’s responsibilities.

Financial crime investigation continues to be a core mission of the agency. In 1997, the Secret Service added a Dutch shepherd named Mike to the Miami field office. The dog’s job: detecting counterfeit money, in a pilot for what would become the Canine Counterfeit Detection Program.

The program was established to help root out counterfeit U.S. currency coming from Colombia, a major source of fake U.S. banknotes. It was hailed as the world’s first use of canines for this purpose.

The doggy dollar detective, as some alliteration-loving Secret Service staffers dubbed Mike, did a bang-up job. In just a one-year span after the program was well established, his work resulted in $5 million in currency being seized and twenty smugglers arrested. The program was so successful that the Secret Service helped implement a similar canine program in Colombia.

—

As part of a counterfeit crew, Mike and his handler would have worked closely with Secret Service agents, since it falls to agents to investigate financial fraud.

But wait! Aren’t handlers agents? Isn’t almost everyone in the Secret Service an agent?

Actually, no. Most people don’t realize that there’s a vital component of the Secret Service called the Uniformed Division (UD). It employs more than 1,300 officers (compared with the 3,200 agents in the Secret Service).

>

The UD is considered the police or security division of the Secret Service. It began in 1922 as the White House Police Force and changed names and missions over time. Dog handlers are part of the Uniformed Division. Canines have been playing an integral role in the Secret Service since 1975.

Uniformed Division officers are charged with protecting the White House complex, the vice president’s residence, and the main Treasury Building and its annex. Chances are that most of the Secret Service “agents” tourists see in the vicinity of the White House are UD officers.

UD officers also protect foreign embassies in Washington, D.C., as well as heads of state visiting the United States. They travel the nation and the world in support of the protectees. But the job is based in Washington, D.C., which makes it appealing to people who want a firm home base. Many who choose to go UD instead of becoming an agent do so for this reason.

Besides the Explosive Detection Team, several specialized units fall within the UD, including the Countersniper Team, Emergency Response Team (with its own canines), Motorcade Support Unit, Crime Scene Search Unit, and bike patrol. Officers can apply to be part of these units once they put in enough time on their initial basic duty.

Agents have an entirely different career path, starting in field offices for several years and then getting assigned to a presidential protective detail, vice presidential protective detail, or dignitary protective detail. Or they may alternate between protective assignments and financial crime investigations.

If you’d like a quick way to tell UD officers from agents, you can sometimes look to their attire. Officers usually wear uniforms, and agents often wear suits. But there are many exceptions to both. It’s not always easy to distinguish the two at a glance. Agents wear whatever the situation dictates. If a president is walking on the beach, an agent may wear a polo shirt and khakis. Depending on the assignment, UD officers may also wear a more casual attire that helps them blend in, especially when in foreign countries.

Soldier Dogs

Soldier Dogs Top Dog

Top Dog Secret Service Dogs

Secret Service Dogs